The continuous wavelet transform (CWT) essentially evaluates a correlation function of the input signal with shifted and scaled Morlet wavelets. A Morlet wavelet is a sinusoidal wave packet modulated by a Gaussian envelope. The spread of Gaussian envelope is what controls the time/frequency balance of the FCWT result.

In contrast to the Short Time Fourier Transform, where the window size does not depend on the frequency, the CWT models a frequency-dependent window size by the frequency depending spread of the Gaussian envelope.1

For a reference frequency \(f\), the Gaussian envelope \(g(t)\) of the wavelet is given by

\[g(t) \sim e^{-\left( \frac{t f}{2 \Sigma} \right)^2}\]

with variance in time \(\sigma_t=\frac{\Sigma}{f}\) which also sets the scale for the effective time resolution of the CWT at frequency \(f\) and a dimensionless parameter \(\Sigma\). The corresponding frequency uncertainty is given by the spreading of the Gaussian in Fourier space: \(\sigma_f = \frac{f}{2\pi \Sigma}\). The time and frequency resolution satisfy the famous time-frequency uncertainty relation \(\sigma_t \sigma_f=\frac{1}{2\pi}\).

The time-frequency uncertainty relation is true for any \(\Sigma\) or frequency \(f\), but we can adjust the parameter \(\Sigma\) to increase (decrease) time uncertainty at the cost of decreasing (increasing) the frequency uncertainty. The “correct” balance depends on your use case.

From uncertainty to resolution

So which time and frequency resolution \(\Delta t\) and \(\Delta f\) can we expect from a certain value of \(\Sigma\)?

The resolution is set by the Gaussian spread which in turn is quantified by the uncertainties \(\sigma_t\) and \(\sigma_f\). Interpreting the Gaussian as a window function, we expect that in order to achieve a certain resolution \(\Delta_t\) the window size needs to be at least equal (or smaller) than \(\Delta t\). Since a Gaussian has infinite support, we need to make a more or less arbitrary decision where the exponential falloff of the Gaussian is close enough to zero for our liking.

In our case, we decide that \(4\,\sigma\) is the effective width of our window function, and so we expect an effective resolution of

\[\Delta t:=\frac{4Σ}{f}\]

and

\[\Delta f:=\frac{2f}{πΣ}\]

Example: Piano keys

Let’s try to understand the meaning of \(\Sigma\) via an example: We would like to analyse piano music, and be able to at least distinguish different piano key frequencies.

We can, for example, check what the resolutions corresponding to \(\Sigma=1\) at the key A4 (440 Hz) is with helper functions that implement the formulas above:

We see now, with \(\Sigma=1\), our frequency resolution at 440 Hz is only 280 Hz! The spreading is way too high to be able to distinguish different keys (the next key A#4 is at 466 Hz and the previous key Ab4 is at 415 Hz), at least we need to be able to resolve the difference, 15 Hz. We can use another helper function to check what the corresponding \(\Sigma\) should be:

sigma_from_freq_res(u(15, "Hz"), u(440, "Hz"))

#> [1] 18.67418and it tells us we need \(\Sigma=19\) or higher. Let’s double-check what that implies for the time resolution:

This means, we can detect those frequencies with a time resolution of 170 milliseconds. A typical very fast piano beat is around 180 beats per minutes (> Prestissimo), i.e. three beats per seconds, and the required time resolution to detect that is at least 330 milliseconds: our time resolution is still below that, so we are on the safe side.2

Let’s compare these settings in practice. As an example serves a simple piano sample playing a couple of 440 Hz notes in the beginning and some simple chords in the end.

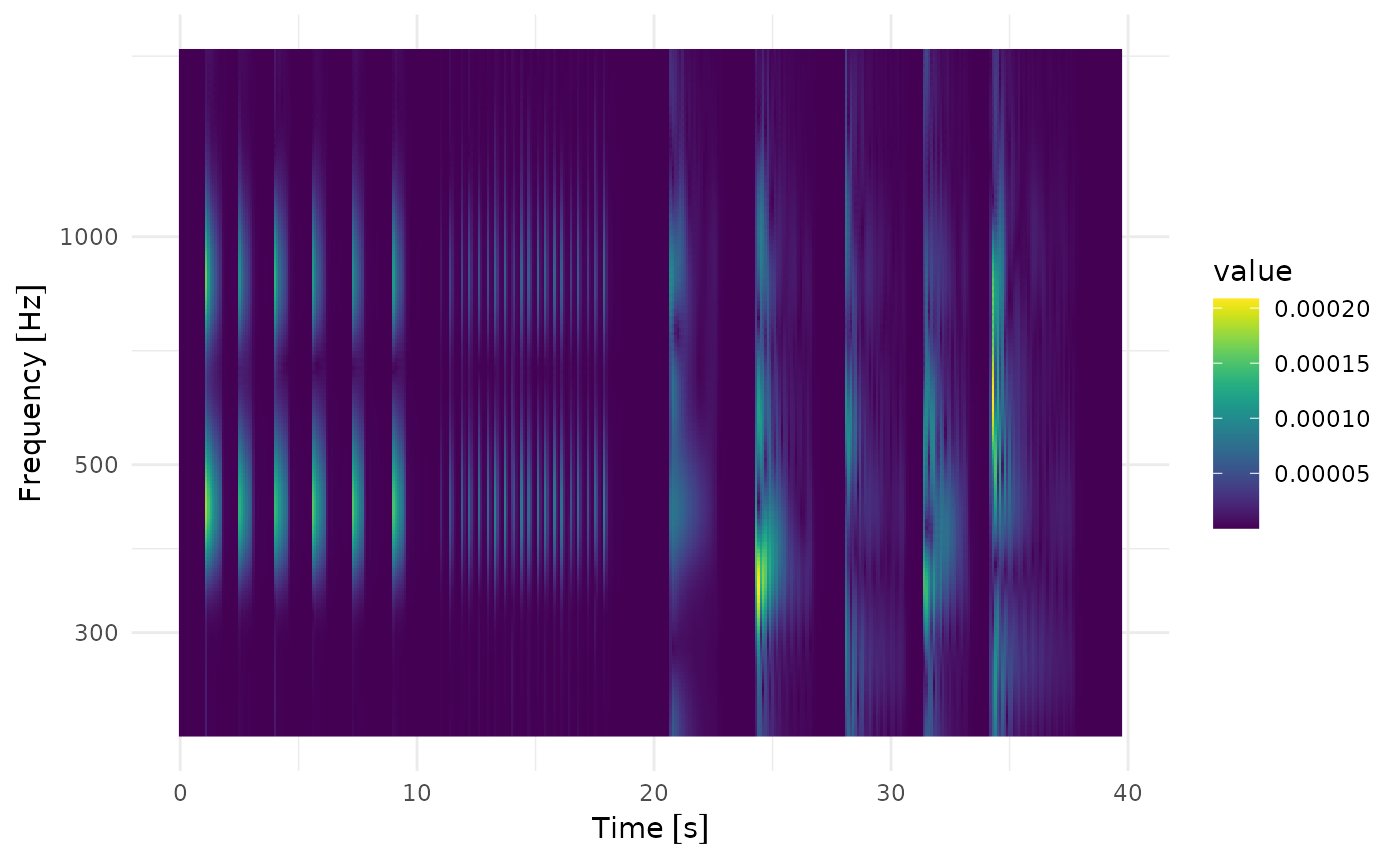

High time resolution, low frequency resolution

library(ggplot2)

fcwt(

ts_piano_sample,

x_sample_freq = u(44.1, "kHz") / 4,

sigma = 1,

y_sample_freq = u(10, "Hz"),

freq_begin = u(220, "Hz"),

freq_end = u(440, "Hz") * 4,

n_freqs = 12 * 5 * 3

) |>

plot()

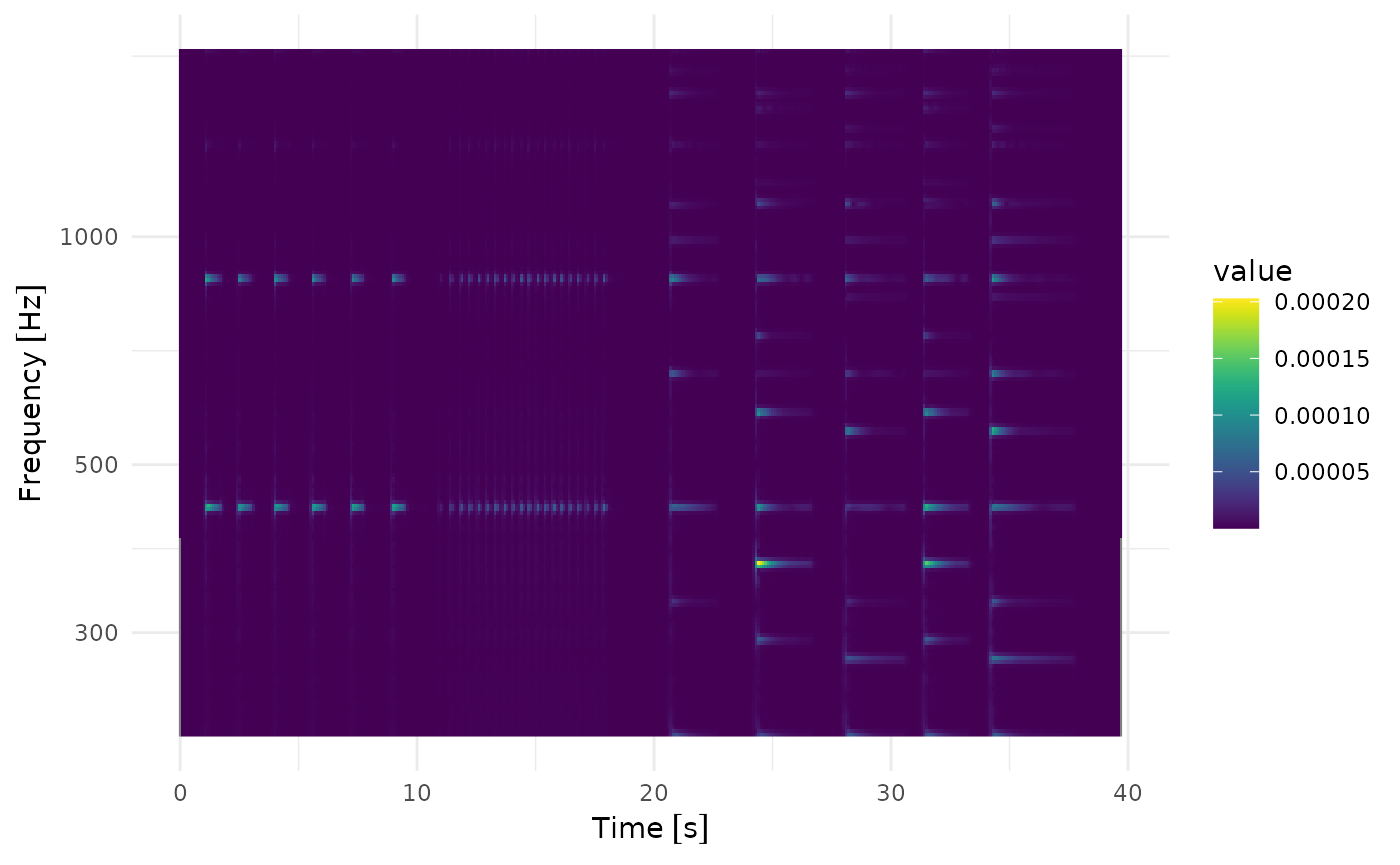

Good middle ground

fcwt(

ts_piano_sample,

x_sample_freq = u(44.1, "kHz") / 4,

sigma = 20,

y_sample_freq = u(10, "Hz"),

freq_begin = u(220, "Hz"),

freq_end = u(440, "Hz") * 4,

n_freqs = 12 * 5 * 3

) |>

plot()

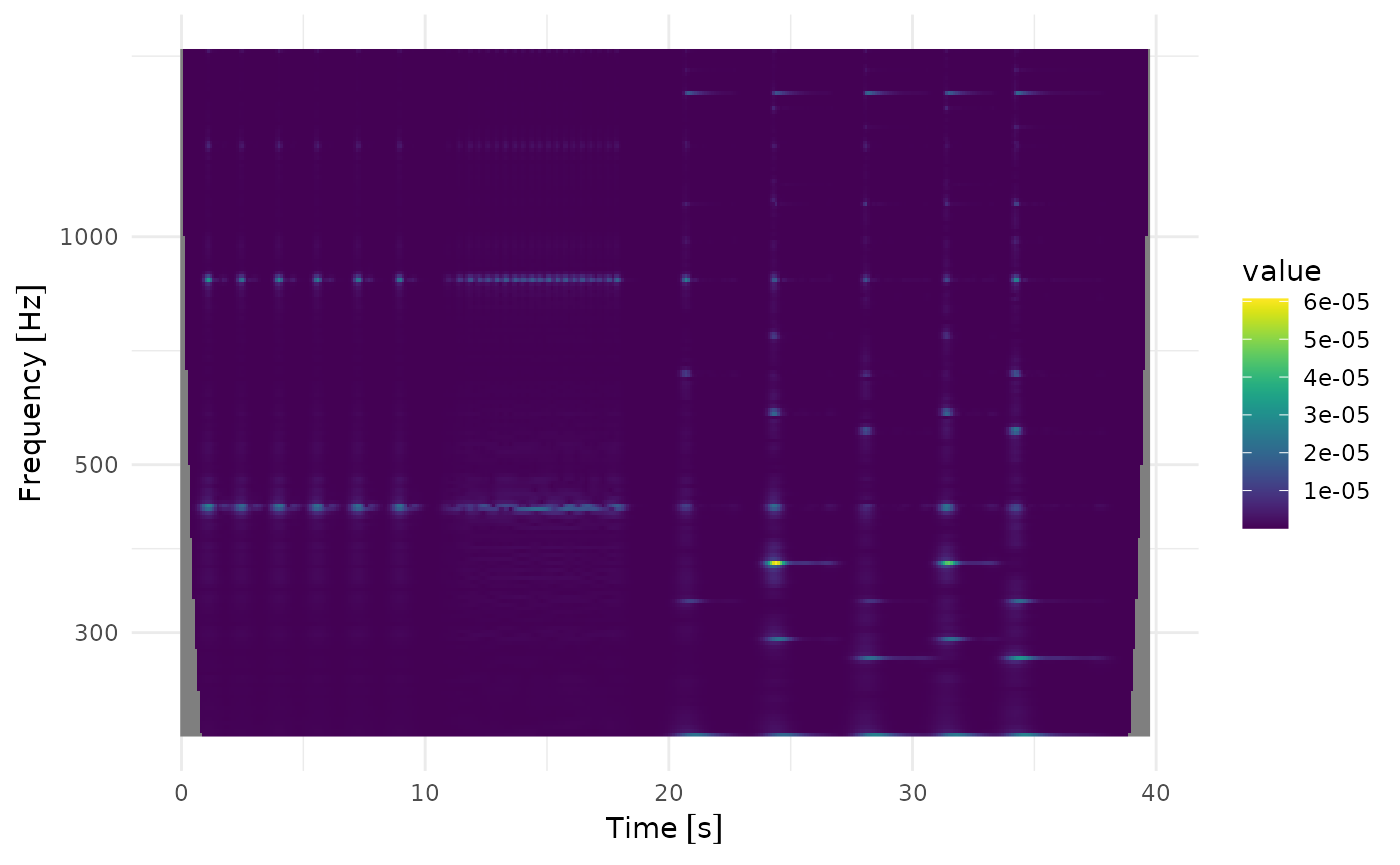

Low time resolution, high frequency resolution

Note that with \(\Sigma=100\) we have

and so we barely have a time resolution of one second. As we can see, we can not resolve the beats between second 12 and 18 anymore:

fcwt(

ts_piano_sample,

x_sample_freq = u(44.1, "kHz") / 4,

sigma = 100,

y_sample_freq = u(10, "Hz"),

freq_begin = u(220, "Hz"),

freq_end = u(440, "Hz") * 4,

n_freqs = 12 * 5 * 3

) |>

plot()

In some way, \(\Sigma\) can be thought of the exposure time of a camera that has to adjusted manually. Is the exposure time too long the picture becomes blurry; is it too short, the picture becomes too dark to see anything. A good balance is key to a good photo.